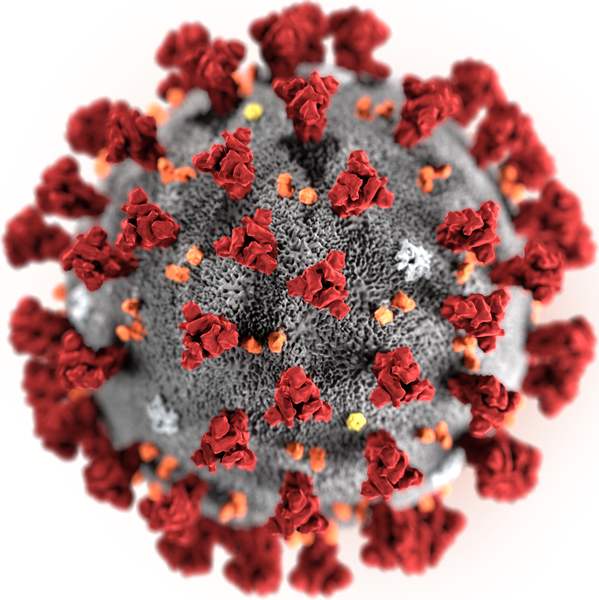

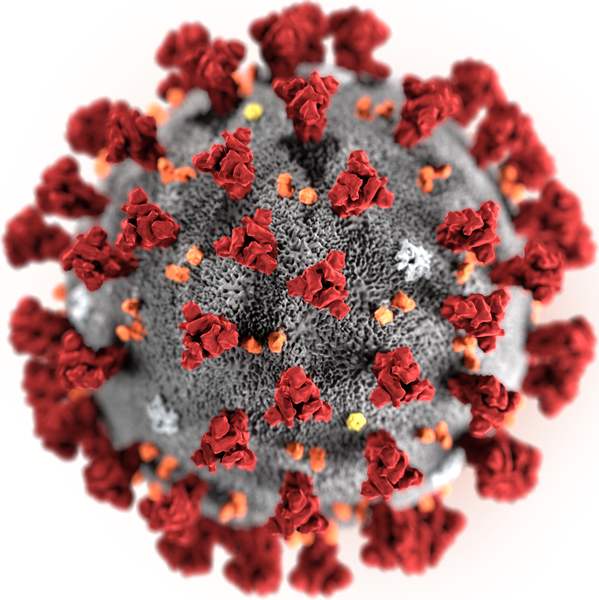

The coronavirus pandemic has caused a wave of job loss, pay cuts, reduced hours, and other adverse financial outcomes for millions of Americans. If you are mired in financial difficulties, you might think about filing for bankruptcy. This may be the right solution for some debtors, but it is an extreme step that is not necessary for everyone. Before deciding to file, you may want to consider alternatives to bankruptcy and investigate sources of assistance that may be available. For example, you may be able to receive unemployment benefits, which have been supplemented by federal funds during the COVID-19 outbreak.

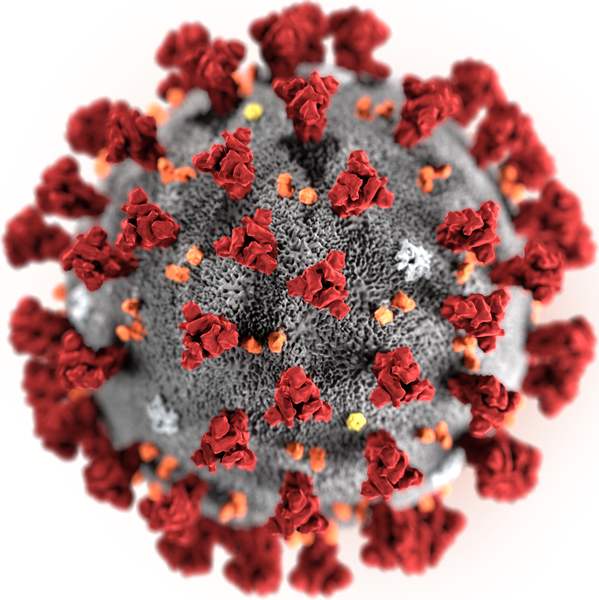

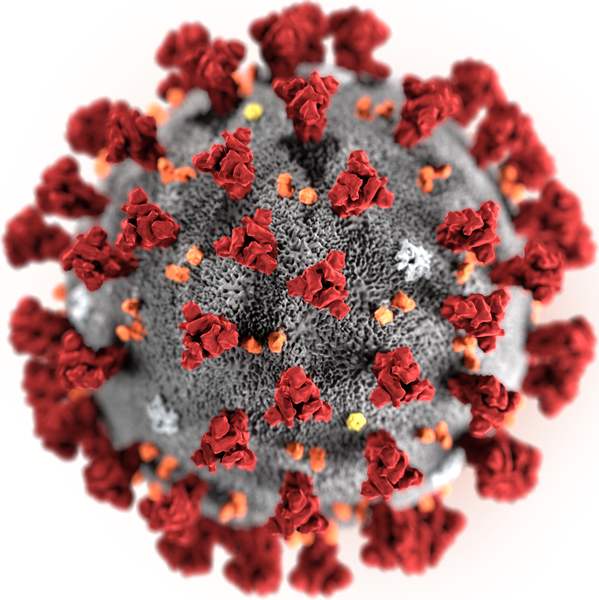

The federal government has frozen foreclosures and evictions involving certain properties for a limited period. It also has deferred student loan payments, and some providers of private student loans may agree to similar deferrals. Mortgage servicers and institutions that provide credit cards and car loans may be willing to adjust the terms of these agreements. (You should make sure to confirm any adjustments in writing if possible.) Many state and local governments have enacted separate protections against evictions, utility shut-offs, and sometimes foreclosures for people who cannot pay those bills. However, these measures generally defer payment rather than eliminating the debt, so you may want to devise a strategy for catching up with debts such as missed rent and utility payments in the future.

Avoiding Bankruptcy

The duration of the COVID-19 outbreak may affect whether you can avoid filing for bankruptcy. If you cannot make regular payments on your bills, after accounting for unemployment benefits and other sources of support, you may decide to defer payments and put aside those funds for necessary expenses. Once the coronavirus emergency resolves, you may have sufficient funds remaining to cover the missed payments, or to negotiate with creditors on payment plans. During recent economic downturns, landlords often have been willing to reduce the amount of missed rent that a tenant owes, and other creditors also have been flexible. They may prefer to settle a debt efficiently and collect at least some funds, rather than risking collecting nothing (or waiting much longer for payment) if a debtor files for bankruptcy.

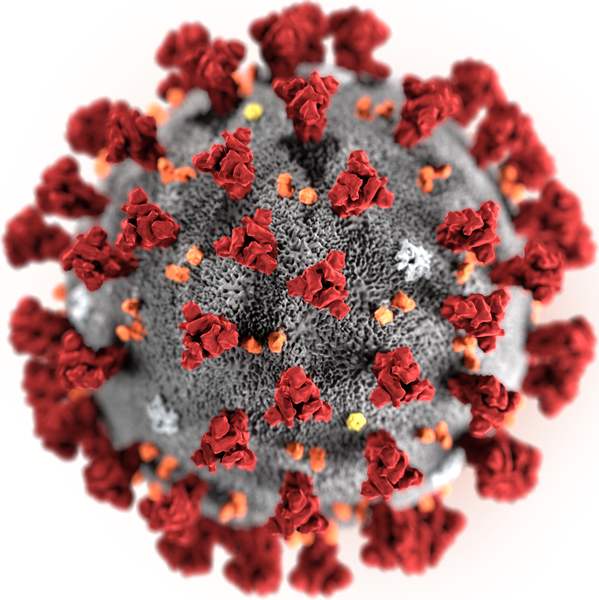

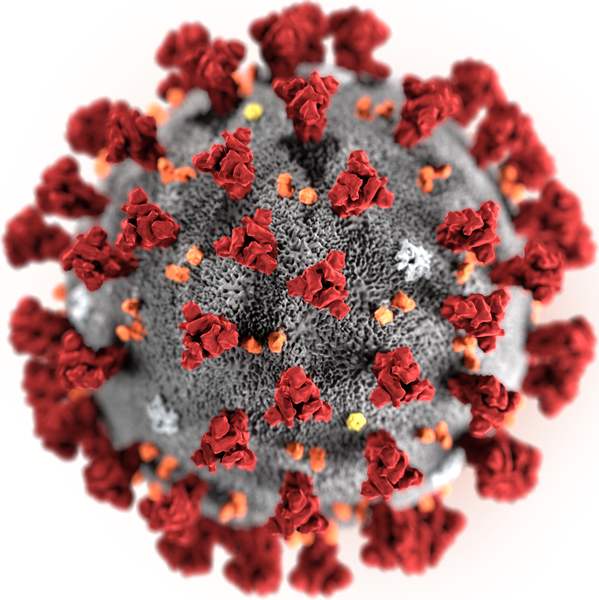

However, if the COVID-19 outbreak does not resolve for a long time, a debtor may not have enough savings to catch up on missed payments or negotiate a viable payment plan. The debtor then may need to file for bankruptcy. Since you will need to pay taxes on any amount over $600 for which a creditor forgives payment, tax liability is another factor to consider in determining whether bankruptcy is the right strategy. If a debtor can reach agreements with some but not all creditors, they may decide to file for bankruptcy rather than paying any creditors. This is because the tax debt related to the forgiven amounts will not be dischargeable in bankruptcy.

Filing for Bankruptcy

While bankruptcy does not eliminate all types of debt, it should eliminate most types of debt that a consumer might acquire during the coronavirus pandemic, such as missed rent, credit card debt, and medical debt. Most individuals file for bankruptcy under either Chapter 7 or Chapter 13. Chapter 7 is a liquidation bankruptcy, which means that the bankruptcy trustee will sell all the non-exempt assets of the debtor and distribute the proceeds to creditors. Debtors can keep certain property that allows them to maintain the necessities of life. Dischargeable debts are automatically wiped out at the end of this process, regardless of whether they are fully paid. Debtors usually must pass a means test to file under Chapter 7, unless their business debt is greater than their personal debt. Sometimes a debtor cannot file immediately after losing their job, since the means test assesses their income over a six-month period.

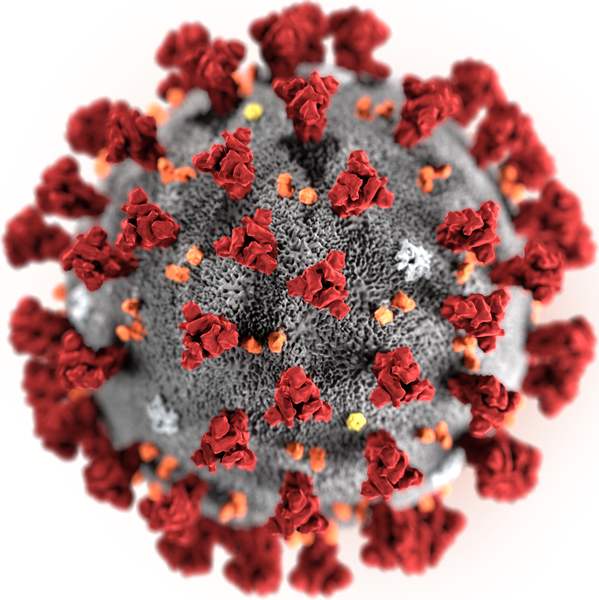

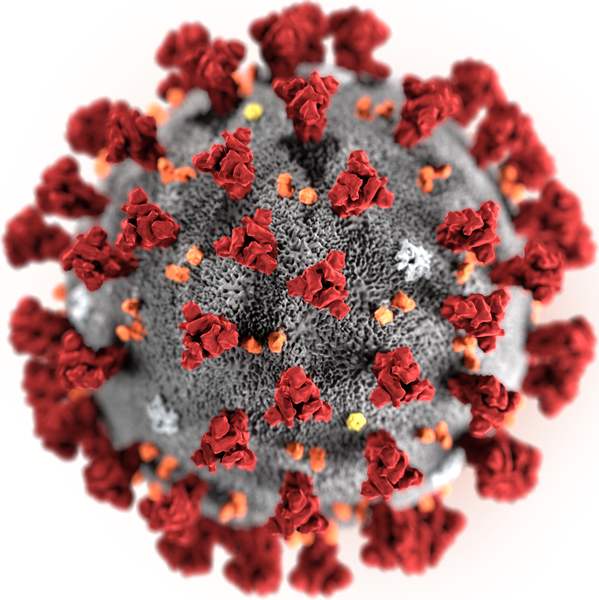

By contrast, Chapter 13 offers relief to people who can afford to pay back their debts over three to five years. They do not give up any assets but instead channel their discretionary income into a repayment plan. Generally, people who file under Chapter 13 have more financial resources than people who file under Chapter 7. The process lasts much longer than Chapter 7, but it can prevent the loss of key assets, such as a home or car. People who have suddenly lost their jobs may struggle to set up a viable repayment plan, though.

Debts accumulated after a bankruptcy petition is filed are not discharged, and you cannot file under Chapter 7 again until eight years have passed since your previous filing. A two-year gap applies to Chapter 13 filings, while separate time limits apply to filing under either chapter after filing under the other. Thus, consumers may decide to wait until they have accumulated all the debt that they are likely to incur before filing for bankruptcy.